A Right or A Duty? A Privilege?

Imagine. If you had a relationship with a something that was absolutely ancient, and so precious that life—including yours—couldn’t survive without it, what would you do to care for and protect it? If it needed food and water and air, would you ensure that it had plenty and the best possible? If it were vulnerable to the ravages of weather—the wind, sun, and rain—would you make certain that it was shielded from harm?

This soil is ancient. The mineral parent rock once sat naked. Time and water, sun and cold broke the rock into stones, the stones into dust. For a very long time the earth sat aging, then the life process started, and living soil was created. Thousands of years of plants have left their condensed energy and captured time stored in the organic matter. Farming it in present time is a relationship with the past.

Imagine the soil has a heart and we’re walking all over it and talking about it. What is this like for the soil? It doesn’t get a say. People walk on it, talking, making human plans, like it is ours to open up and do as we want. Think how long this has been going on here. Since they broke the prairie off of this land, one hundred forty years of doing this to soil.

What was it like for Ole Olsen the first time to pick up handfuls of virgin prairie loam? What did it smell like? What happiness did he feel? If we knew what we know now, what would we do different?

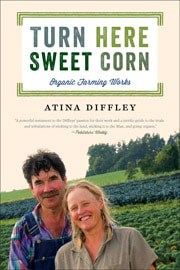

If soil was virgin, what is farming? Do we choose a love affair, or is it a coarse taking? — Excerpt Turn Here Sweet Corn: Organic Farming Works

As organic farmers we grew Sudan grass and clovers, oats, hairy vetch, and rye to add organic matter to the soil, absorb rain, hold soil in place, and feed the microbial life. In working the land we avoided cutting grooves that rain could rip open and start erosion. Winter cover provided shelter from wind and water erosion.

Farm soil is a wild animal held in captivity. Living in the soil are more undomesticated species than can be found aboveground on the entire planet. This soil life has simple needs: food, air, water, and shelter. Just like every other species. Prevented from caring for itself, it lies at our mercy, dependent on our long-term vision and integrity. Its future capacity is determined by our judgment. Anytime we open up the land—when we remove its protective cover of grass and forb, brush and tree, when we lay the soil bare, exposed to the elements— we embezzle its ability to command its own wellness.

Opening land is a covenant. — Excerpt Turn Here Sweet Corn

A covenant—in law is defined as an agreement. Do we have a contract with land, and what does it say? Who is responsible for what? If the land feeds us, must we in turn feed it? In Theology a covenant is an agreement that brings about a relationship of commitment between God and his people. Is spirit part of this? What commitments do we have to land and nature? What does it mean to “own” land? Is it a right or a duty? A privilege?

When we began a five-year search to purchase land after suburban development removed all life from our living-breathing farm I reached a deeper understanding of soil-land and our human relationship.

“There is no such thing as a new farm,” Martin says. “All Minnesota farms are used. That’s the dilemma.”

I had never thought about it this way before; it is an entirely different perspective. I was focused on getting away from the bulldozers, on putting together a home and outbuildings, fields and greenhouses, creating a new family farm, and this time we will be the owners. “This is a little like buying a used car,” Martin says. “We need to look for all the things the seller doesn’t point out. But unlike a used car, we can’t take it for a test drive. We have to know clearly what we want and need before buying.”

He adds, “We need to look at how the water moves and how the neighbor’s runoff comes on and affects it. It won’t be looking to see if there has been erosion, but how badly. We have to look for old dumps—every farm had one. If we are lucky, it will just be a pile of broken glass bottles and tin cans. Usually it’s near the rock pile, at the edge of the woods or the mouth of a gully. They can have old chemical containers that are empty now but weren’t when they were discarded; there might be appliances or engines leaking fluids. In land ownership, it’s not the person who polluted who bears responsibility and liability for cleanup, but the present property owner.” — Excerpt Turn Here Sweet Corn

All life on the planet needs food and water to exist. All species eat and every species is eaten in turn. Even more profound is the basic truth that we all come from the same earth; our bodies consist of the same minerals and elements as the plants and insects and birds.

Whether soil is an inch thick or as deep as I am tall, we are utterly dependent on it. We are also utterly dependent on complex ecosystems and biological diversity. This is as true for the gardener and farmer as it is for those who live in a world of man-made structures and concrete streets. Every one of us has a relationship to land and soil and nature through our food—every time we eat. What a gift! And what a responsibility!

We all eat and the Laws of Nature apply to all of us. We feed the soil and the soil feeds us. We preserve nature and nature preserves us. Our well being is intimately connected to that of all other life on the planet. What we do in nature we do to ourselves.

© Atina Diffley 2012

Subscribe to Atina Diffley’s Blog

Read Turn Here Sweet Corn| Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound | University of Minnesota Press

Read Atina Diffley's Blog: What Is A Farm?

Subscribe By Email. It’s Free

Enter your email address:

Worshops & Consulting

Visit Organic Farming Works LLC for Workshops and Coaching/Consulting with Atina and Martin Diffley.